The Conversion of Henri IV of France

Chapter 4 : Against the Odds

The King is dead, long live the King! But which King? By right and by the explicit testimonial of Henri III, Navarre succeeded to the throne as Henri IV. The Pope, the League, the King of Spain, declared an excommunicated Protestant could not be King of France. They welcomed the succession of Navarre’s Catholic uncle the Cardinal de Bourbon as Charles X – a childless man of sixty-two and Navarre’s prisoner.

Henri IV needed troops but he was not cash rich. The mourning he wore for Henri III was the same mourning – the same clothes – that Henri III had worn for his mother Catherine de Médicis, cut down to fit the shorter King.[1] His chances against the League, which received Spanish and Papal subsidies were slight.

However, rather than retreating to his heartland in the south west – safety - Henri IV moved into Normandy, the richest province in France. The new leader of the League, the Duke of Mayenne,[2] pursued, to take Henri IV back to Paris in chains. In the Battle of Arques in September 1590, Henri IV outmanoeuvred Mayenne and forced him to retreat. Elizabeth I sent 4,000 troops to help Henri IV. And, the first sign of cracks in the Catholic monolith, Venice declared an alliance with the Protestant King of France.[3]

A second battle followed at Ivry, fought on 14th March 1590, closer to Paris. On his helmet Henri IV wore a large white plume – an ostrich feather - with an even bigger white plume attached to his horse’s head.[4] He made himself conspicuous to his men and to the enemy. Again he was outnumbered by Mayenne’s troops. Again he won. On 7th May 1590, seven weeks after Ivry, The Cardinal de Bourbon – Charles X – died. Another obstacle had gone.

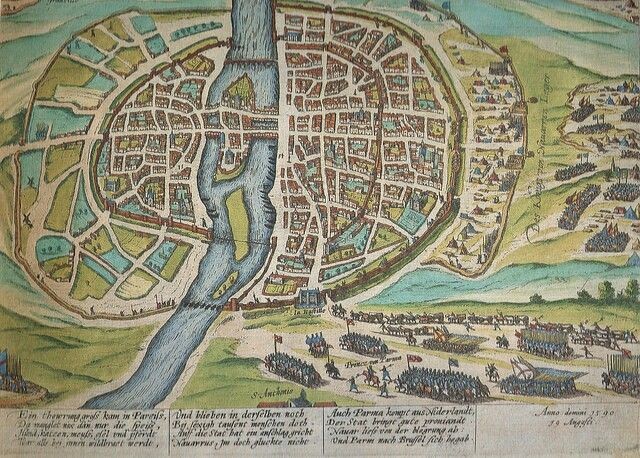

Henri IV went on to besiege Paris. He withdrew when the Duke of Parma left Flanders – on the order of Philip II - and delivered food and a Spanish garrison to the city, but the King had made his mark as a winner. During the next two years, League forces supported by Spanish troops under Parma kept Henri IV away from Paris. Then in December 1592 Parma died, as the result of a wound he had received months before. The loss of Spain’s great general changed the balance.

France had now been at war with itself for an incredible thirty years. Mayenne, a man of less aggressive temperament than his murdered brothers, called the States General to discuss the situation. These were therefore Leaguer States General, but even so times had changed since the last meeting of the States General in 1588. The French were desperate for peace.

Henri IV had prepared the ground with early friendly overtures. On 4th August 1589, two days after the death of Henri III, he issued the Declaration of St Cloud, in which he pledged to maintain the Catholic Church of France, and said that he would himself seek religious instruction from a national Church council. On the same day leading members of the Catholic nobility swore an oath of allegiance contingent on the King’s later conversion.[5] Henri IV proved his good faith by continuing to run the Royal Chapel – the King’s Catholic religious household – under Renaud de Beaune, Archbishop of Bourges.

Yet he was still a Huguenot, and he was not trusted. The King’s cousin, the Cardinal de Vendôme, started negotiations with the new Pope Gregory XIV about support for his own candidacy as Catholic King of France. The result was that Gregory in March 1591 proclaimed a second excommunication of Henri IV and all his supporters including Vendôme.[6]

Nonetheless Henri IV was seriously considering conversion. His problem was later summarised by his Huguenot lieutenant, the future Duke of Sully – who claimed the credit for advising conversion. The princes and grandees of France were at each other’s throats. They were filled with anger against him (Henri IV). His foreign supporters (the Dutch, Elizabeth I) were losing interest. It was impossible to see a settlement of France that was not Catholic because France, a very large country, was predominantly Catholic.[7]

The Leaguer States General met on 17 January 1593 and discussed a proposal for the election of a Catholic king – Guise? - which did not find much support. Instead they voted in favour of a Catholic conference for more discussion. There was also a motion from loyalist Catholics to support the legitimacy of Henri IV and by obedience encourage him to convert.

Philip II now showed his hand. His ambassador, Feria, told the States to show their gratitude. What this meant was soon explicit. Philip wanted his daughter Isabela elected Queen of France in her own right – through her mother she was grand-daughter of Henri II – then married to her cousin the Archduke Ernst, so that France would have a new Habsburg dynasty. The States did not take up this proposal. The King of Spain still had plenty of troops to enforce his will but did not have Parma to lead them.

All in all, the States were for the first time something close to friendly to Henri IV but he still had time to act of his own volition – essential politically. On 17th May the Archbishop of Bourges announced that Henri IV would convert to Catholicism. On 18th May the King wrote to the clergymen who would help instruct him. All this was done without seeking the approval of the Pope, and deliberately so. Henri IV wanted to convert as a French patriot, not beholden to any foreign prince.

[1] Catherine de Médicis died in January 1589. See Michelet p 425 for the mourning.

[2] Another Guise brother

[3] Michelet pp 430-1

[4] Michelet p 432

[5] Wolfe pp 56-7

[6] Wolfe p 106

[7] Sully Mémoires (vol 1) (Paris 1827) p 434