The Conversion of Henri IV of France

by Dominic Pearce

Chapter 1: The State of France

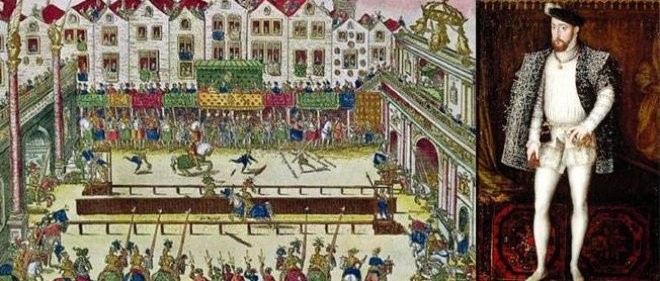

In the last quarter of the sixteenth century France was the sick man of Europe. A terrible decline started on 30 June 1559, when King Henri II decided on one more joust at a tournament in Paris, held to celebrate the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, signed with Spain. His opponent was Gabriel de Montgomery, Captain of the Scots Guard. Montgomery’s lance splintered on impact. A fragment pierced the King’s eye. Septicaemia set in. It was nearly two horrible weeks before Henri II died.

Happily he had four sons to succeed him, unhappily all were young. His successor as king was his eldest son François, fifteen at the time, and just recently married to Mary, Queen of Scots. François II was not a minor according to French law (which provided that the king reached his majority at the end of his thirteenth year). Nonetheless he was a teenager who came to the throne too soon. With the agreement of his mother, Catherine de Médicis, François II delegated the business of government to his wife’s uncles, François, Duke of Guise, and Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine.

François II died in 1560, a year after he became King. He was succeeded by his ten year old brother Charles IX. During the royal minority Catherine de Médicis was Regent, the wife whom Henri II humiliated by his open affair with the ageless, grasping Diane de Poitiers. Charles died in 1574. He was succeeded by the third brother Henri III (twenty-two) who married Louise de Lorraine, a kinswoman of the Guises.

This was the second marriage which tied the Guise faction to the throne.

Who were the Guise? The father of Duke François was Claude, the first Duke of Guise and first nationalised Frenchman in the family. He was the younger son of the sovereign Duke of Lorraine. The Guise were not therefore considered truly French by the local nobility. They had royal connections, they were rich, but they needed a cause to attract support. They made themselves Catholic champions.

Duke François has the distinction of starting the French Wars of Religion, the longest civil war in European history. On 1 March 1562 he led an attack on an unarmed Protestant (Huguenot) congregation worshipping - legally and peacefully - outside Vassy in north east France. The following year he was killed by a sniper during the siege of Orléans, a city occupied by Huguenot troops in reaction to the Vassy massacre.

The worst single atrocity of the Wars of Religion – of the century – the Massacre of St Bartholomew’s Day in 1572 was started by an assassination attempt on the Huguenot Gaspard de Coligny in Paris, the man Henri de Guise held responsible for the death of his father (François). It was probably Henri who ordered the attack. In the ensuing bloodbath at least 5,000 Huguenots, men, women and children were killed in Paris and the provinces [1].

Henri de Guise then united Catholic watchdog groups across France into a national body, the Holy Catholic League. Henri was a charismatic populist, known as Scarface (‘l e balafré’) after a wound received during the Battle of Dormans (1575) that caused one of his eyes to weep involuntarily from time to time. With the League he had a national organisation behind him dedicated to the destruction of French Protestantism, ‘… but as time passed the question of the royal succession was brought into it, and the Pope and King of Spain became involved .’[2]

King Henri III had no children, so his heir was his brother François, Duke of Anjou. But on 10 June 1584 Anjou died after a tubercular infection – in reality he was killed by the doctors who applied their failsafe remedy, bleeding – leaving the throne of France open to the next heir, Henri de Bourbon. It was this development that attracted the dangerous attention of Philip II and the Pope.

[1] For the numbers see Treasure the Huguenots p 174

[2] Sully Mémoires (Paris 1827) p 146 n