Royal Splendour

Chapter 1: Introduction

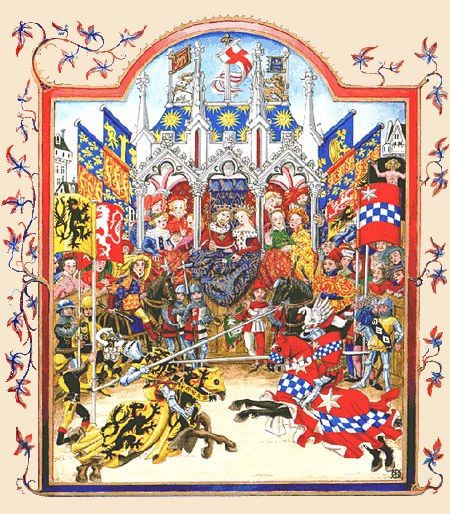

In the late mediaeval and Renaissance period, kingship and nobility was portrayed, in part, through conspicuous consumption and displays of ostentation. There was little industry to invest in and so surplus funds were spent on buildings, pageantry, clothes, jewels and employment of large numbers of retainers. Heraldry, chivalry and symbolism were important components of everyday life, in a world in which literacy was limited and visual representations were paramount and coats-of-arms, mottoes and badges were incorporated into everything.

For the Tudor monarchy, display was even more important than it had been for their predecessors – Henry VII’s claim to the throne was shaky, so he bolstered it with public displays that were loaded with symbols indicating his royal descent – red roses (not much associated with Lancaster until his reign); Beaufort portcullises; references to his supposed descent from King Arthur; the construction of Richmond palace, and his chapel at Westminster, and the huge spectacle that surrounded three of the great occasions of his reign – the investiture of his son Henry, as Duke of York, the marriage of Arthur, Prince of Wales, and the marriage procession of his daughter, Margaret.

Similarly, in Scotland, although money was much less readily available, James IV spent lavishly on promoting a vision of monarchy on a European scale – sumptuous clothes, and massive building programmes at Linlithgow and Holyrood being part of it.

Their successors, too, spent extravagantly. Henry VIII’s court was a byword for splendour and James V spent the dowries he received with his two French wives, on building programmes at Stirling and on great quantities of clothes and jewels. Elizabeth I, is, of course, famous for her fabulous wardrobe, although she was much more financially conservative than her father had been, and, like Henry VII, tried to limit expenditure by the crown, whilst maximising that of her courtiers.