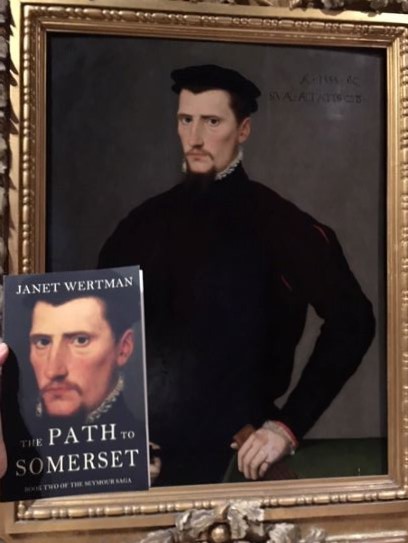

Portrait of Edward Seymour by Antonio Mor

by Janet Wertman

For hundreds of

years, the general public knew only two basic choices for a likeness of Edward

Seymour: the younger Edward of the Holbein painting who personified the Spanish

ambassador’s description of him as “dry, sour, and opinionated,” or the older,

more benevolent Edward captured by the “English School” portrait.

But in fact there

has always been another choice: a rendering of Edward by Antonio Mor that is

one of the gems of Sudeley Castle’s art collection. The portrait, between half-

and three-quarter length, offers an insightful view of the man who was rising

to power during the ten years before Henry’s death. A gaunt-faced Edward

Seymour faces slightly left while his eyes engage the viewer directly. His hair

is short cropped, receding into a widow’s peak and covered by an unadorned

black velvet cap. His dark blue eyes suggest suspicion atop the prominent bags

that betray his exhaustion. His lips press together under a trimmed moustache

for an overall impression of intensity and diligence.

Besides his

face, only his hands stand out, held confidently and resolutely at hip level. The

long and tapered fingers of his left hand hold a brown leather glove and rest

on a table covered in a Tudor green tablecloth; his right hand is curled around

the hilt of his sword. His only jewelry is a gold signet ring on the little

finger. The glove, the sword and the ring are more serviceable than flashy;

this is a man of action.

The rest of him

is swathed in black and blends into the somber background. Here, too, luxury is

minimised. His neck and wrists are sheathed in small

ruffs of lace, and his scarlet shirt is not pulled through the slashing in his

doublet or shoulders. Such restraint suggests tight control over not only his

cloth but his emotions as well. Painted in 1535, before his sister Jane had

caught the King’s eye, it also shows a man who knows his place… or at least, the

one he had then.

That it hangs in

Sudeley Castle is fitting because of the connection to the Seymour family: on

the death of Henry VIII, Thomas Seymour became Baron Seymour of Sudeley and

lived there with Katherine Parr. Equally fitting is the attribution to Mor, the

painter whose “compelling realism” gave us the Queen Mary I we know so well and

scores of other European dignitaries. Admittedly, the portrait is not included

in lists of Mor’s works, and the broad strokes of Mor’s biography don’t fully

lend themselves to the designation (while Mor did famously come to England to

paint Mary, that didn’t happen until around 1554 – two years after Edward was

executed). Still, I believe: I can absolutely point to two ways that Edward

could have sat for the artist. First, Mor’s earliest paintings hang in the

Palais de Beaux-Arts de Lille, not far from where Edward spent time in France

during that period. Second, Thomas Seymour was sent to the Netherlands (where

Mor grew up) to keep him away from Katherine Parr during the last royal

marriage, returning to England just as Henry was dying and Edward was seizing

power. If Mor came with him, he would of course have spent time at Sudeley.

Admittedly,

there are two major problems with this second theory. First, it does not fit as

well with the date (the portrait was painted in 1535, Henry died in 1547). More

important, the painting did not arrive at the castle until the Victorian era,

when it was purchased at a Christie’s auction by Marianne Brocklehurst for her

sister, Emma Dent, who was Sudeley’s chatelaine and an avid collector of art

and artifacts.

The purchase is detailed in a delightful letter that Marianne wrote to Emma and transcribed here. Apparently there was some uncertainty over whether the portrait represented Thomas or Edward (they really wanted it to be Thomas!). The price was lower than expected, only £150, primarily because there was a slight crack in the panel (though off the face), but also because the National Portrait Gallery was starved of funds at the time and not prepared to bid aggressively.

My dear Emma,

Mr. Booth

waited for your reply to telegram saying likeness uncertain until 12 o’clock.

It did not arrive – so she followed me to Christies, mentioned she’d got two engravings

to look at at Colnaghi’s [the oldest commercial art gallery in the world,

established in 1760]. She and I decided it was the Protector Seymour as the picture

is painted 1535 sua aetatis 28 which is all right. We telegraphed to you at a

quarter to one and the picture was sold at a quarter to four. Two minutes after

the picture was sold your telegram to Mr. Woods arrived – In the dire

uncertainty I sent Mr. Woods a line to say I would be responsible and I have

bought the picture for £150. You can

have the first refusal at the price – but if you don’t want it, leave it to me.

Mr. Armstrong (who married Oneta Lesdu) [let’s just assume I got this wrong] was

in the room at the time of sale – he stood to agreed he said “it was a very

cheap picture and he would have bought it but it had a crack in the panel.” I

had the picture on the floor this morning. The crack I don’t consider of any

consequence as it is away from the face somehow so.

Mr. Woods

said Mr. Scherff wanted to buy it for the National Portrait Gallery – but as he

has not come again, he supposed he could not screw up the committee to the

point his expression was “they are starved out” – Woods thought it would fetch £300. I said he had sold one of the Duke of Alva this year (by

Antonio Mor) for £1,000. From

Colnaghi I got to know that W. de Zoete bought it forty years ago from a dealer

called Ferrar - a very well-known man considered a first authority. And he

seems to have named this picture Seymour. Colnaghi agreed with me it was not

Thomas – I am very sorry it is not, but such a beauty, just come from Madrid. I

could not resist. It may be Seymour of Sudeley after all as he was only 28 in

1535 and he might have grown a bigger beard afterwards when fashion changed. I

should think you can tell by the date for a certainty.

Still, the most important development in the portrait’s history came in the present day, when the Ashcombe family decided to open Sudeley to the public and share Emma Dent’s wealth of treasures with the world. The family is committed to the continued preservation of the castle, its treasures and the ongoing restoration and regeneration of the gardens – and it shows in the improvements they continue to make in the exhibitions. This amazing painting – which truly captured the Edward Seymour of my own mind’s eye – is just one of many important sights that needs to be seen. Thankfully, they all can be.

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset

Family Tree