Sizergh Castle

A hidden gem in the Lake District

Visiting

The Castle is set off the main road, with the ticket office and shop on the edge of the car park. Both shop and cafe serve the usual National Trust fare. The food is good, but not exciting – a range of soups, sandwiches and cakes, with a couple of hot dishes with local resonance, in this case, Cumberland sausages and Wensleydale cheese. The shop has National Trust books and household wares.

Passing through the shop, the immediate area of interest is the bank barn. A bank barn is a two-storey structure built into raised ground with animal quarters on the lower floor, and an upper floor for machinery, reached via a ramp.

A hundred yards to the north of the barn is the main entrance to the castle. Spread out before you is a U -shaped series of stone buildings incorporating the original mid-14th century tower and the Great Hall. The tower would have been the heart of the family's living quarters. Known as a “solar tower" as the principal room, or “solar", would have had window openings to catch as much sun as possible, it would have been defensible, but not primarily built with warfare in mind.

The mediaeval Great Hall was replaced in the 1560s by a new hall, with the family accommodation on the upper floor and an open space underneath. It was modified again in the late 19th century by enclosing the lower floor, with enormous doors on the east and west sides to allow a carriage to enter and deposit its passenger directly into the enclosed court.

This innovation was for the comfort of Lady Edeline Sackville, who came from the more balmy airs of Knole in Kent to marry Sir Gerald Strickland, and wished to alight from her carriage indoors, safe from the Westmoreland winds.

Modern visitors enter through the great door created for Lady Edeline.

Inside is a small lobby for ticket and coat collection, then into the main hall which is dotted with relics of the illustrious career of Sir Gerald Strickland, a senior member of the Colonial Service in the 19th century. There are Maori spears and the cases of stuffed marsupials so dear to the Victorian collector's heart.

Beyond the corridor, the castle is a warren of rooms leading off each other in unexpected ways. The complex political and financial history of the family meant that although "improvements" were made through the ages, they were always in the nature of a bolt on, rather than a clean sweep and replacement with a grand mansion in the Palladian style.

The first room is still used as the family dining room at Christmas. On the first floor of the solar tower it was originally the main living space. It is not a huge room, having been divided into two parts in the 1560s, but the diamond shaped panelling is interesting, as is the massive Victorian dumb waiter hiding in a cupboard to the right of the fireplace.

Walking through the dining room you enter a pleasant sitting room, the Queen's Room, overlooking the eastern grounds. The name recognises the elaborate carving of Queen Elizabeth I's arms over the fireplace, dating from 1569, and intended as a mark of loyalty, necessary for the still-Catholic Stricklands to display. The ceiling is plastered in traditional Elizabethan fashion.

Through the dining room again, you are led into the huge drawing room. Originally the mediaeval hall, then the Elizabethan Great Hall, it was fitted out in the mid eighteenth century as a drawing room, with new windows and alcoves for stoves on the inside wall, now filled with china and other artefacts.

Processing through the Drawing Room, there is a further room known as the Stone Parlour. The current decoration dates from the 1740s – the most interesting feature being the lovely stone-tiled black and white floor.

Opposite the Stone Parlour is the Old Dining Room, lined with original Elizabethan lozenge-shaped panelling as well as having a traditional plasterwork ceiling, also in lozenges.

In this room is an enchanting painting of one of the Strickland ladies of the 1840s, Gasparine de Finguerlin, as well as another ornate manifestation of the arms of the Sir Walter Strickland of the 1560s. Leading off of this is an even lovelier Elizabethan room with traditional linen-fold panelling, dating from the early 16th century but reused here as part of the 1560s remodelling.

On we go, up the north stairs, to arrive at the Banqueting Hall. This is the second storey of the solar tower and was the subject of nineteenth century alterations to fit current ideas of a mediaeval hall. The upper floor was cut away, to reveal the interior of the roof, a splendid collection of Tudor beams. A faux minstrel gallery was also added in the 1940s. The floor however, is original – ancient oak boards that show the wear of 800 years in their worn markings! I couldn't help a little thrill as I thought of Katherine Parr walking over it in her black velvet slippers.

There are various pieces of Elizabethan dining furniture to admire – a long refectory table and seating forms. Exiting the Banqueting Hall, one enters the piece de resistance of Sizergh – the fully panelled inlaid chamber. The panelling is the epitome of 16th century inlay and carving, under an intricate stone plastered ceiling. The ceiling and the inlaid panelling belong to the Victoria and Albert Museum, having been sold for hard cash in the late 19th century. Fortunately, the V & A was unable to actually move the ceiling, but did take the panelling away. It was restored on permanent loan in 1992. All traces of the Elizabethan work are of such high quality, and in such an advanced style for the 1560s, that one cannot help wondering where the Sir Walter Strickland of the time came across such sophisticated Italian architectural taste. With all due respect to sixteenth century Westmoreland, it was not a hotbed of the avant-garde!

Outside the castle, you are treated to a most unusual garden. Instead of herbaceous borders and knots, Margaret Hulton, second wife of Sir Gerald Strickland, spent a great deal of her fortune on having a huge limestone rock garden created.

History of the Castle and Strickland family

The Stricklands were settled near Carlisle until, in 1239, Sir William married Elizabeth Deincourt, who inherited the Sizergh estate. It was William and Elizabeth's grandson, Sir Thomas, who probably built the great solar tower in the mid-1300s and took up permanent residence. He honoured his grandparents' memory by including a coat of arms of Strickland and Deincourt into the external stonework. From this period, the heads of the family were called Thomas or Walter in turn.

The family's fortunes rose during the French Wars, and Sir Thomas (died 1455) had the honour of carrying the banner of St George into battle at Agincourt. The Stricklands were clients of the great Neville family, Earls of Westmorland who were second only to the Percies of Northumberland in power in the North. The main function of the Northern gentry was to follow the earls into war against the Scots, which the various Sir Walters and Sir Thomases duly did. Unfortunately, the rivalry between Neville and Percy meant that their followers were almost as frequently required to take part in wars between them, as against the Scots. This conflict contributed to the bloody striving between Lancaster and York that erupted in the Wars of the Roses.

The Stricklands followed the junior branch of the Nevilles into support of York. The Sir Thomas who died in 1497 was knighted on the field of Tewkesbury following the victory of Edward IV. Despite this support of York, the Stricklands suffered no disfavour under the conciliatory Henry VII, and the Tewkesbury knight's son, Sir Walter, was invested as a Knight of the Bath at the marriage of Prince Arthur to Katharine of Aragon in 1501.

The following two Sir Walters (missing a Sir Thomas!) continued the activities of their forefathers and fought against the Scots in 1523 and again in the 1540s, in the War of the Rough Wooing. However, the leg-up in Tudor politics that the Stricklands received in the first half of the sixteenth century was based on advantageous marriages.

Sir Thomas, the veteran of Tewkesbury, married Agnes Parr, sister of Sir William Parr, of Kendal. In the way of the closely intermarried Northern gentry, the families stayed close and thus, when Sir William Parr's grand-daughter became the final consort of Henry VIII, the Stricklands were not forgotten. The other helpful match was the marriage between Sir Walter (son of the Knight of the Bath) with Katherine Neville, heiress to some 1,200 acres of a goodly estate in Thornton Bridge, Yorkshire.

This Katherine was the Lady Strickland who gave a home to Katherine Parr after the death of her first husband, Sir Edward Burgh. Katherine Parr's sojourn here is not definite – it is first mentioned by Agnes Strickland in her “Lives of the Queens of England" as a family anecdote (although Miss Strickland was from another branch of the family and not resident there). No subsequent biographer of the Queen has disputed it and it is perfectly likely, given that Katherine Parr was cousin to Sir Walter Strickland and that Katherine Neville's second husband, Henry Burgh, was the uncle of Sir Edward.

The money that Katherine Neville's estate brought into the family enabled the vast expansion of the Castle in the 1550s-80s by her son, Sir Walter.

This Sir Walter, whom we may refer to as Sir Walter the Builder, spent considerable amounts on the development of his property, sweeping away the mediaeval hall to the north of the solar tower, and replacing it with a Great Hall in 16th century style, as well as building two long ranges of buildings that contained a Long Gallery, and numerous bedrooms. He was aided in his plans by his second wife, Alice Tempest. She was so pleased with the plans for refurbishment that she and her third husband, Thomas Boynton continued the works, during the minority of her son, a new Sir Thomas. The Boyntons commissioned the marvellous inlaid chamber.

Unfortunately, Sir Walter the Builder's life was not all about spending his mother's inheritance. He was drawn (unwillingly, of course – it is hard to find anyone who did not protest their innocence) into the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. He was pardoned, and conformed to the religious changes over the next twenty years but seems to have come under suspicion as a secret Catholic in the 1560s. However, given that the majority of the North leaned towards the old religion, active persecution was not pursued, at least in the early part of Elizabeth's reign.

The son of Sir Walter the Builder was MP for Westmoreland in the last Parliament of Queen Elizabeth's reign, and found favour under James VI & I, with a Knighthood of the Bath being bestowed at the new king's coronation. This Sir Walter took to gambling and he further risked the family's fortunes by marrying a committed Catholic, Margaret Curwen. He died during the infancy of most of his seven children and Margaret brought them up in the old faith.

In the centuries following the Tudor period, the financial and political fortunes of the Strickland family ebbed and flowed in a manner typical of many English gentry families.

The Strickland family supported King Charles I during the Civil War and, although they did not have their estates confiscated by the victorious Parliamentarians, heavy fines had to be paid, which, together with gambling debts, took a terrible toll on the estate.

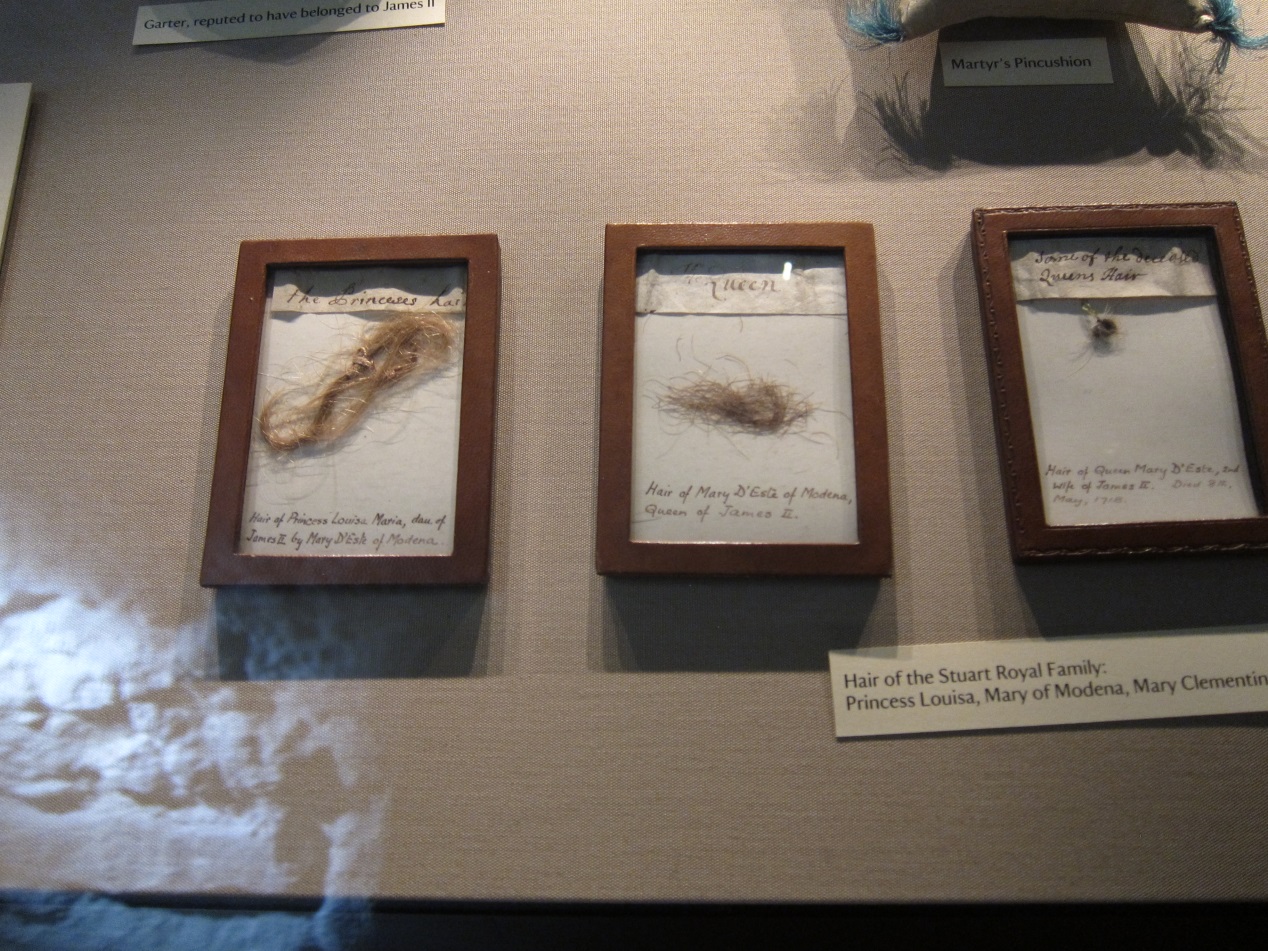

Sir Thomas and his wife were members of the inner circle of James, Duke of York, later James II. Lady Strickland was present at the birth of James Edward Stuart, Prince of Wales in 1688 and was appointed his Under-Governess. Following his abdication, the Sir Thomas and his wife chose to accompany James II and his wife and son into exile in France.

The family fortunes improved considerably in 1762 when Sir Charles Strickland married a great heiress, Cecilia Towneley (1741-1814). Her fortune helped to restore the family, and some of it was spent on the creation of the Georgian Drawing Room.

However, fortunes ebbed again during the early 19th century with Sir Charles' grandson, Sir Walter, who spent much of his time in France, and all of his time in financial difficulties. It was he who sold the inlaid chamber to the V & A, and, eventually, the whole estate to his cousin, Sir Gerald.

Sir Gerald was a prominent Victorian politician, Prime Minister of Malta, Governor General of Western Australia and Victoria and Member of Parliament for Lancaster before moving to the House of Lords as Baron Strickland. Sir Gerald, despite eight children by his first wife, and a second marriage, had no surviving sons. His eldest daughter, the wife of Sir Edward Hornyold, inherited. They and their son, Lieutenant-Commander Thomas Hornyold-Strickland gave the castle to the National Trust in 1952. The Lieutenant-Commander's widow still resides here, together, on family occasions with her children and grandchildren.