Bess of Hardwick: From Farm House to Palace

Like most women, Bess never left England, but she travelled regularly between her native Derbyshire and London, and to the estates of her third husband in Somerset, as well as with the court. Many of her journeys related to supervision of her magnificent constructions at Chatsworth and Hardwick.

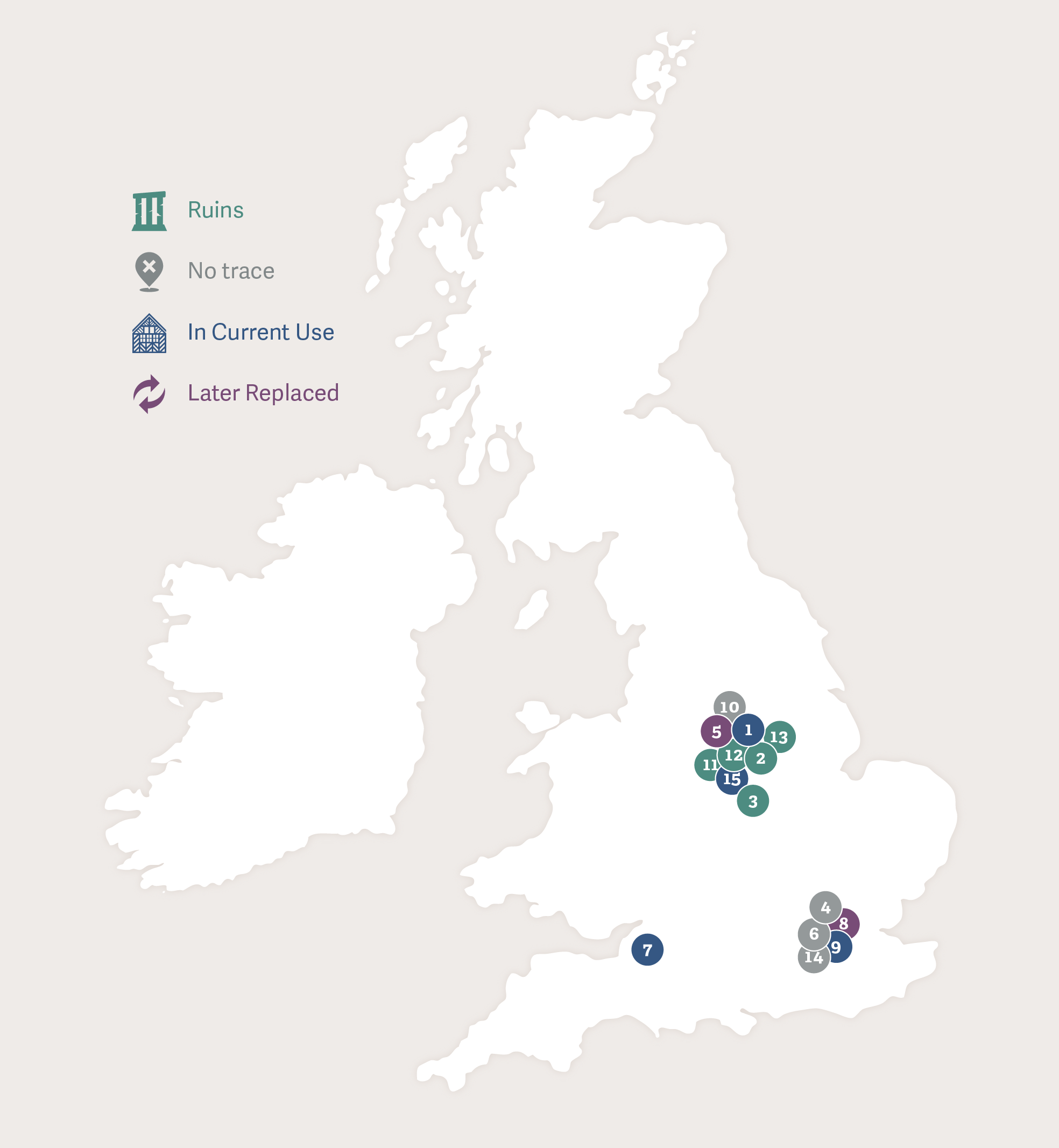

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

Bess was born into a comfortable, but not grand, farmhouse called Hardwick Hall (1), just on the Derbyshire side of the county border with Nottingham. Although her father died when she was a child, leaving a minor heir, Bess’ mother managed to retain the house for the younger siblings to live in. Mrs Hardwick remarried and had three more children, which probably made for a lively childhood. In later life, Bess lent money to her brother, James, secured on the Hardwick estate. When he died, a bankrupt, she bought out his other creditors. In 1587 she began a major refurbishment programme. The remains of this, known as Hardwick Old Hall, are in the care of English Heritage.

But the Old Hall was not enough for Bess’ status as a countess. In 1590, a whole new hall was begun, based on designs by Robert Smythson, the most important architect of Elizabethan England. He worked on Longleat, and probably on Burghley House as well. These great ‘prodigy houses’ were symbols of wealth and power, built to last.

The majority of the building materials for Hardwick came from Bess’ own land. She even built a glass factory, to create the magnificent ‘Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall’.

Today, Hardwick can be reached from Junction 29 of the M1, or from the A617 Chesterfield to Mansfield Road.

Bess left her childhood home when she was about twelve, to enter the household of Anne, Lady Zouche at Codnor Castle (2). Lady Zouche had been a maid-of-honour to Queen Anne Boleyn, so this would have been a great opportunity for Bess. In fact, there is no hard evidence of Bess being in the Zouche household, but circumstantial information has led her biographers to think it probable.

Codnor Castle was one of the great mediaeval castles of England. Originally owned by the de Grey family, ownership fell into abeyance in 1496 between various branches of the family. Henry VII purchased the castle from the heirs for his son, Henry, Duke of York, later Henry VIII. When he became king, Henry VIII sold it back to Lord Zouche, one of the heirs of de Grey.

In 1634, the castle was sold and largely dismantled. The ruins are in the hands of the Codnor Castle Heritage Trust, which is hoping to protect them from further deterioration. Bess probably lived at Codnor from about 1539 – 1543. It is the likely location for her meeting with her first husband, Robert Barlow, although, as the Barlows were another Derbyshire family, she may already have known him.

Bess was widowed before her husband came into his inheritance, and disputes over her dower meant that she was once again obliged to earn her living. She was employed in the household of Lady Frances Grey (nee Brandon), Marchioness of Dorset at Bradgate (3), in Leicestershire.

This was a huge step up for Bess – Lady Dorset was the King’s niece, and, whilst Henry had little time for her husband, Henry Grey, Marquess of Dorset, the two were still prominent in court circles. Like Bess’ first employer, Lady Zouche, the Dorsets were religious reformers. Bess quickly became close to the whole family – all her life, she treasured an agate ring that Lady Dorset gave her, and a picture of the Dorset’s oldest daughter, the luckless Lady Jane Grey.

Bradgate has been enclosed parkland for well over 800 years. The house that Bess lived in with the Dorsets was planned by Sir Thomas Grey, 1st Marquess of Dorset, the half-brother of Queen Elizabeth of York. The actual building work was done by his son, the 2nd Marquess and completed around 1520. It was constructed of the fashionable, and extremely expensive, red brick.

It was at Bradgate that Bess met and married her second husband, Sir William Cavendish. He was considerably older than her, with two previous marriages behind him and at least two living daughters, but nevertheless, the couple soon developed a close working partnership that speedily increased their joint wealth. Bradgate descended in the Grey family, who continued to live in it for another two hundred years after the mid-sixteenth century. After 1739, it was replaced with a new house, and fell into ruin. These ruins can be viewed today – they are in the care of the Bradgate Park Trust, which also looks after the extensive woodlands. It can be reached by taking the A50 from Junction 22 of the M1.

After they were married, Bess and Cavendish lived mainly in London, in a house near St Paul’s, and also at an estate called Northaw (4). Northaw village remains – tucked into the Hertfordshire countryside, just north of the M25. The manor of Northaw was originally a possession of the Abbey of St Albans. At the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was granted to William Cavendish and his then wife, Margaret.

In 1552, Cavendish and Bess exchanged the manor, together with all their lands outside Derbyshire, for a large parcel of crown lands in their home county. It is suggested by Bess’ biographer, David Durant, that the exchange was made in case a change of government resulted in questions about the status of former monastic lands. There is no trace today of the Cavendishes’ home, and even the church dates only from the nineteenth century.

William Cavendish was probably originally from Cavendish, in Suffolk, but he was a younger son, so had no inheritance there. He and Bess were happy to acquire lands in Derbyshire. The manor of Chatsworth (5) was in the hands of the Leche family, probably relatives of Bess’ mother, whose name was Elizabeth Leake (a homonym) and who married, as her second husband, Ralph Leche. When Ralph Leche’s nephew, Francis, died without heirs, it provided an excellent opportunity for William and Bess to buy the estate. It was subsequently augmented after the sale of Northaw, as noted above.

Bess and Cavendish clearly had a vision of founding a great dynasty, in which they proved remarkably successful. To achieve the status they dreamed of, a great house was an important part of the visible success they needed to show. They began to build at Chatsworth, and this would prove to be one of the most rewarding projects of Bess’ life. She spent many years improving and beautifying the house – perhaps in hopes of a visit from Queen Elizabeth.

Whilst Elizabeth never did visit, her favourite, the Earl of Leicester did, and Mary, Queen of Scots was held there from time to time, when other locations needed to be cleaned.

Chatsworth was entailed on her eldest son, Henry Cavendish, but Bess retained a life-interest in it and spent a good deal of time there, particularly after she and her fourth husband became estranged. The current Chatsworth House, one of the greatest of all England’s ‘Stately Homes’ has almost obliterated Bess’ house, although it is built around the original courtyard plan she designed. The house is still the home of Bess and William’s descendants, the Dukes of Devonshire.

Of course, such an ambitious couple as Bess and Cavendish could not spend all their time in Derbyshire. William was frequently in London, and in 1555, he arranged to rent a house at Brentford (6) from Sir John Thynne, where Bess could spend the winter with him. She was expecting her sixth child, and did not like to be parted from her husband. Thynne proved to be a good friend to Bess. When Cavendish died in 1557 and was accused of peculation of Crown funds, he helped her both by leasing the Brentford house to her again, and arguing against a bill in Parliament that would have bankrupted the widow.

The Brentford Manor that Bess knew was replaced in 1628 by a truly delightful Jacobean house – well worth seeing. Now called Boston Manor, it is on Boston Manor Road, and is in the care of the London Borough of Hounslow. It is open from time to time during the summer months or for exhibitions, and details of opening times may be found here.

Sir William Cavendish was buried in the Church of St Botolph-without-Aldersgate (8), near his mother and his first wife. A church was first built on the site in the twelfth century, and it received extensive improvements in the 1570s under Lord Mayor, Sir William Allen, who was born in the parish. By 1725, it was in such poor condition that it was demolished and rebuilt in the style of Wren. The structure was badly damaged by an IRA bomb in 1993, but repaired. A number of prominent late sixteenth century figures were buried here, including Lady Mary Keyes (née Grey), daughter of Bess’ friend Frances, Duchess of Suffolk.

When Bess married Sir William St Loe in 1559, the couple became embroiled in a long-running dispute with St Loe’s brother and sister-in-law, Edward and Margaret St Loe. The nub of the matter was the status of Sutton Court (7), in the curiously named village of Chew Magna, Somerset. When Bess first visited, perhaps thinking that she and St Loe would live there, she ordered various improvement works to the early fifteenth century house. In the event, Sutton was awarded after St Loe’s death to Margaret St Loe for her lifetime, and Bess did not return.

Sutton Court was extensively rebuilt in the 1850s, and then converted in the late twentieth century to flats.

Like Sir William Cavendish, Sir William St Loe was also buried in London, but his resting place was Great St Helen’s Church, Bishopsgate, London (9), alongside his father. This church was once attached to a Benedictine convent, but, after the house was dissolved in 1538, it became the parish church. St Helen’s too, was severely damaged first by a bomb in 1992, and then by the 1993 bomb, which also killed three people. It has now been restored.

On her marriage to Shrewsbury, Bess’ chief marital home became Sheffield Castle (10). The castle was at the heart of the settlement that grew up around the rivers Don and Sheaf, in Yorkshire. A timber structure was first erected in around 1100, which was burnt by Simon de Montfort in his rebellion against Henry III. It was rebuilt around 1270, and the owner, Thomas de Furnival, received a licence to crenellate the new stone structure. The castle came into the hands of the Talbot family when Maud Neville, 6th Baroness Furnivall, married John Talbot, who was created Earl of Shrewsbury in 1442. He is the ‘Old Talbot’ of Henry VI.

The first Earl instigated wide-ranging repairs to the castle, which had two courtyards, with the usual range of buildings – tower, hall, chapel, bakehouse etc. When Bess’ husband, the 6th Earl died, the castle, along with the Barony of Furnivall, passed to her step-son, Gilbert Talbot, 7th Earl, who was also her son-in-law. Gilbert and his wife, Mary Cavendish, only had daughters, so the Barony of Furnival fell into abeyance between their three daughters. Sheffield passed with Alathea to the Howard Earls of Arundel. It fell to Parliament in the Civil War and was eventually slighted.

The site is now largely covered with other buildings, but a small portion of the remains can be seen below the Castle Market, by prior arrangement. The Friends of Sheffield Castle promote the archaeological investigation of the site

It was largely at Sheffield that Mary, Queen of Scots was kept, although initially she was taken to one of Shrewsbury’s other manors – Tutbury Castle (11), on the Derbyshire/Staffordshire border. Tutbury, once owned by John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, was, by the mid-sixteenth century, damp, badly drained and completely unsuitable for a queen. Shrewsbury was also concerned that the local inhabitants were ‘corrupted with Popery.’

The castle’s strong point was its defensibility. Bess was at Tutbury from time to time during the period of Mary’s captivity – when the Queen first arrived in early 1569, Bess had had to furnish the place quickly by sending some of her own household goods from Sheffield Castle. Today, the ruins of Tutbury Castle, which can be visited by the public, are looked after by a trust

Another of Mary, Queen of Scots’ prisons was the Shrewsbury manor of Wingfield (12), near Alfreton, Derbyshire. Dating from the mid-15th century, the house was purchased by the 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury in 1456 on the death of its builder, Ralph, Baron Cromwell. Mary was kept there in 1569, and again in 1584 and 1585. It was at the centre of the Babington Plot, in which Sir Anthony Babington, a member of a prominent Derbyshire family well-known to Bess, attempted to hatch a plan to rescue the imprisoned queen.

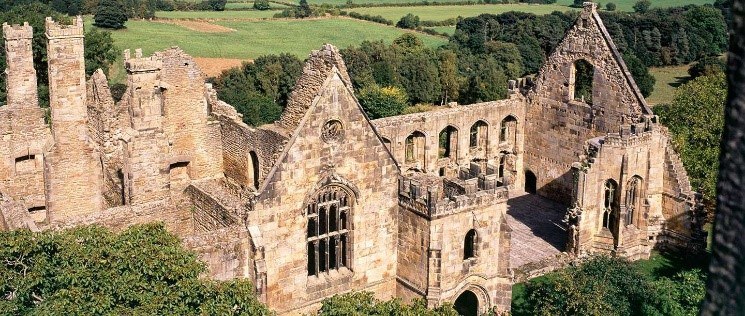

Wingfield was damaged during the Civil War, after which it was sold to Immanuel Halton, who and stripped away much of its stone and other materials to build a new house. This was abandoned in the late eighteenth century.

The ruins of Wingfield are cared for by English Heritage, but can only be visited by pre-booking.

Another of the great houses that Shrewsbury and Bess owned was Rufford Abbey (13). Rufford, once a Cistercian house, was acquired by Shrewsbury following the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Located in Nottinghamshire, it was a convenient place for Bess to meet Margaret, Lady Lennox, who had been forbidden from travelling within 30 miles of Mary, Queen of Scots. There, whilst Lady Lennox was being nursed by Bess, having been struck down by a convenient sickness, the two encouraged the speedy marriage of their children, Lord Charles Stuart, and Elizabeth Cavendish, incurring the wrath of Elizabeth I.

Shrewsbury and Bess extended the twelfth century property significantly, and it passed to their joint grand-daughter, Lady Mary Talbot. The Elizabethan house was transformed in the late seventeenth century, and today is in the care of English Heritage and Nottinghamshire County Council.

Of course, a wealthy couple like Bess and Shrewsbury needed a town house in London. They owned Shrewsbury House (14) in Chelsea. The exact location of the property is uncertain, but it was probably near Cheyne Walk. There are records of George Talbot, 4th Earl, and Francis, 5th Earl, staying at Shrewsbury House during Henry VIII’s and Edward VI’s reigns respectively. It was at Shrewsbury House that Bess and Shrewsbury effected some sort of reconciliation on Queen Elizabeth’s orders in 1586, after which she was ordered to reside at Wingfield where she largely remained until after Shrewsbury’s death.

Bess retained Shrewsbury House, presumably as part of the marriage settlement, and it passed to her son, William Cavendish. He was created Earl of Devonshire, and Shrewsbury House became attached to the earldom until it was sold in 1643. It was demolished in 1813.

The Earl of Shrewsbury died in 1590, and was buried in the Church of St Peter’s in Sheffield, now known as Sheffield Cathedral. The origins of the church probably date to around the same time as Sheffield Castle, with additions and demolitions taking place over the centuries. The Talbot Chapel contains not just Bess’ husband, but other members of the family. Shrewsbury’s tomb has a model of both his wives on it, but, whilst his first wife, Lady Gertrude Manners, is buried with him, Bess is not. Despite her figure being on the tomb, the epitaph omits all mention of her.

For unknown reasons, Bess chose to be buried in All Saints (Allhallows, as it was called then) Church (15), Derby, now the Cathedral, rather than beside any of her husbands, or her father, who was buried at the church local to Hardwick, Ault Hutnall, and where she had been baptised.

Bess began the design and construction of her impressive tomb during her lifetime, but directed that her funeral ‘be not over-sumptuous, or otherwise performed with too much vain and idle charge.’ Despite this, she left £2,000 to cover the costs. She was interred on 4th May 1608 following a sermon oration by the Archbishop of York. Above the vault is a life-sized monument and a plaque on the wall commemorates her (although it dates from the time of her grandson, the Duke of Newcastle). The vault houses more than three dozen of Bess’ Cavendish descendants.

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Bess of Hardwick discussed in this article.