Tudor Dress

Interview with the Tudor Roses

We met Emma Feury and Darren Wilkins of The Tudor Roses to find out more about them, and to learn from their astonishing knowledge of Tudor dress and daily life.

TT: Tell me about Tudor Roses. How long have you been going, and what do you do?

TR: We’ve been around for about four years. We dress in Tudor costume that is as authentic as we can make it, and go to events at places like Hampton Court Palace, and Ingatestone Hall. We may go in character – Darren is sometimes Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, or Sir Thomas Seymour, Katherine Parr’s husband. Emma has played all of Henry’s queens at different times. Other times, we just go as general members of the court. Unlike some other re-enactors, we step out of character to explain to people what we are wearing.

TT: What gave you the idea?

TR (Emma): I was going to an Anne Boleyn Tour, and we were invited to dress up. I wanted to do it as well as I possibly could so I researched it, and I really enjoyed doing it, so I did it again. Then Darren came up with the name and built the website www.thetudorroses.co.uk It’s just gone from there, really. There are six of us now.

TT: How often are you at events?

TR: There’s probably something every weekend over the season – we do a lot at Ingatestone Hall, and Hedingham Castle, both in Essex, and sometimes at Sudeley Castle, in Gloucestershire. As well as Hampton Court, of course.

TT: How do you research your costumes?

TR (Emma): It’s really important to us to understand how, and why, the clothes were made in a particular way. It’s no good thinking like a twenty-first century person, you have to think like a Tudor person. Just a word or a line in a book will mean hours of research. For example, mufflers. I saw one mentioned and my first thought was a hand-muff, but actually, I read more and investigated and discovered that they had mufflers quite like ours – a woollen scarf round the neck and throat. Often, when you see clothes in TV shows, they are not that authentic to the period.

TT: Can you tell me how men and women dressed from the inside out?

TR (Darren): Men’s clothes were really heavy. Everything hangs from the neck. First you have the linen shirt.

TT: Did men wear pants?

TR (Darren): We’re not certain. Pants have been found in other countries – linen on a drawstring, which is where you get the word “drawers” – but there is no mention of them in England. But, why would anyone write it down? I think they probably did, as their underclothes were the only clothes that could be washed.

So, the shirt goes on first, then the doublet. The doublet is the part that you see at the front, with the typical slashing for the shirt to come through. The “lower stocks” (where “stockings” come from) come next. They have linen bands sewn to the top, and are tied onto the doublet. Then come the upper stocks – the part that look a bit like shorts. They are tied onto the doublet as well.

Then the codpiece.

TT: Yes, the great codpiece debate!

TR: They were big, not just as a sign of virility, but because they were used as purses and to keep things in – like a pocket.

The doublet might have sleeves or not, depending on whether the next layer, the jerkin, had sleeves. The jerkin is the origin of the waistcoat, and goes over the doublet. Jerkins in the early Tudor period were V-necked, but this broadened out to a U-shape (as seen in pictures of Henry VIII in the 1530s) to show more of the doublet and shirt.

On top of that, comes the gown. Gowns were long in the early 1500s – lower calf. Then by the 1530s-40s they were about knee-length. They got shorter and shorter over time.Earlier gowns had long sleeves that were turned back, but later gowns had short sleeves.

TT: And what about the women?

TR (Emma): There were up to five layers. The first was the smock of linen, which might have no sleeves, or cuffed or uncuffed long sleeves. It was low over the bust. For modesty (or warmth) the lady might wear a fine partlet over the smock which went up into a small collar.

Under the smock were the stocks, held up with garters. Over the smock came the petticoat. Earlier petticoats went up the back but were cut right down at the front, to prevent bulking up the chest area. By the 1560s they were just on the waist, like modern petticoats.

Next came the kirtle. The kirtle was very firm and tight, and might have reeds in it to stiffen it. All the cleavage you see on Hollywood is not authentic – they flattened the bust as much as possible. Up until the late 1530s the only part of the kirtle that was visible, was the line you see round the neckline, often with jewellery. The open V-shape was not common until the time of Katherine Parr.

TT: Didn’t they wear stays or corsets?

TR (Emma): No. The kirtle was so stiff, they didn’t need to. Everything is so tightly tied that the whole of the upper part of the body is kept in. When I am wearing the costume, I don’t feel hungry because the stomach is pressed flat.

Over the kirtle came the gown. Originally, it laced up at the front, and over the lacing was the stomacher – a pane of cloth that was pinned over the lacing and down the sides under the arms. Eventually, the stomacher started to be sewn under one arm, stretched over the gown lacing and pinned under the other arm. Then, in later years, back fastening gowns came into fashion.

If you were expecting, you left the gown unlaced at the front.

The sleeves of the gown might be fitted all the way to the wrist, or, if you were wearing the long, hanging sleeves, the front sleeve would be tied in at the elbow and the hanging sleeve added over it.

Another thing you see on films that isn’t really correct, is the very stiff Spanish farthingale. When Katharine of Aragon brought it over in 1501, the English women hated it, and just wore gowns flowing. It wasn’t until Katherine Parr was queen and introduced a sort of adaptation, called the English farthingale, that the skirts were held out stiffly.

TT: What about the big cart-wheel farthingales of Elizabeth’s time?

TR (Darren): They were fashionable because of the way they danced then. The man needed to put his arm under the woman, so the skirt had to be held out to allow him to lift her. In earlier times, there wasn’t any lifting.

TT: Was it possible to dress yourself?

TR (Darren): A man could dress himself. If he was careful, he could leave most of the ties in place then climb into them – sort of like a Tudor onesie!

TR (Emma): You could dress yourself, although with difficulty. For women who couldn’t afford someone to help, all of the clothes lace up at the front. But for noble women, you really need someone to help you. And that is part of the display element – “I’m so rich, I have people to dress me.”

TT: Are the clothes very difficult to wear?

TR (Emma): Not as difficult as you’d think. I can drive a car in my Tudor costume, and they rode (astride – they didn’t use side-saddles) and walked and so on in them. Of course, the clothes in the paintings are their best clothes – they would wear something more practical for every day.

TT: How do you manage going to the loo?

TR (Darren): Once you’re dressed, there isn’t much chance of it – that is why the morning ablutions were so important. Once you’re tied into your stocks and doublet, you can’t get out in a hurry.

TR (Emma): As I said before, you just don’t feel hungry or thirsty, so you don’t usually need to.

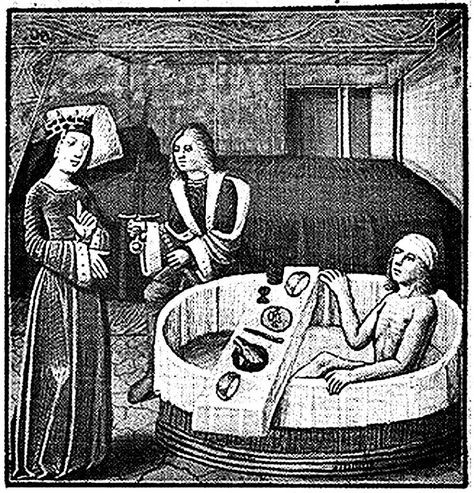

TR (Darren): Whilst we’re on hygiene, they did bath! Henry VIII had a bathroom with hot running water at Hampton Court, and I’m pretty sure he would have used it after hunting. But they didn’t strip to wash – they washed themselves through their shirts or smocks – the linen was abrasive and gave them a good scrub. Apparently, demons would get in if they took off all their clothes!

TT: Was there much difference in how children and adults dressed?

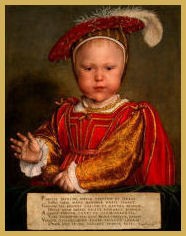

TR (Emma): No, if you look at the picture of Edward VI as a two-year old, he is dressed just like an adult.

TR (Darren): Although usually boys wore dresses more or less until they could handle a sword and ride – at any time between about 8 and 12, they would start to wear men’s clothes.

TT: What were the shoes like?

TR: Fairly plain, with just a bar over the front, but without heels. They could be slashed too, to show the fabric. Men and women both wore long boots for hunting, up over the knee.

TT: And of course, the hoods?

TR: The early hoods, worn by Elizabeth of York, were called church hoods. They came completely forward, over the ears, and you can’t hear anything or see without turning your head.

The gable hoods sit a bit further back, and you can see, but it is still difficult to hear. You didn’t show your hair – partly maybe for modesty, but partly it was kept out of the way for hygiene reasons – you are less likely to get fleas or lice in it if it is covered. At the back of the hood, the fall was in two parts, sometimes pinned up.

The hair was parted in the middle then woven into plaits with linen strips. The plaits were then pinned to the top of the head, a linen coif placed over them and the hood on top of that, with a strip of material completely hiding the hair. Some women even plucked the hair at the front to make sure none showed. Then, later, the hair might be left down, but it would be tucked into a snood at the back.

The hoods were made of buckram (cloth stiffened with something like egg-white or glue) and wire.

It’s not true to say that the french hood only came in with Anne Boleyn. Pictures of Mary, the French Queen, Henry VIII’s sister, show her wearing them earlier, and they would have been seen at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520.

TT: Are you always authentic from the inside out?

TR (Emma): There are different levels. We have some costumes that are completely authentic, and others (suitable for very wet conditions) that are more of a half-way house. So we might make an authentic style gown in a fabric that is washable. The fabrics the Tudors used were very expensive – and they still are. I’ve lost one gown from getting it completely waterlogged.

Typically, the kirtle would have a border of black velvet sewn round the bottom that could be replaced when it was worn or too dirty.

TT: Do you make the clothes yourself?

TR (Emma): I make mine. It took me about four days to make a gown. I am doing blackwork too (the fine black embroidery you see on shirts). It takes ages – about an hour to do half a centimetre. We are trying to work out whether it was sewn directly onto the shirt, or onto a separate piece of cloth that could be moved from shirt to shirt – probably it was detachable, although maybe Henry could afford to have it on all his shirts.

TR (Darren): I order mine from a specialist. I have an everyday black velvet set and I’ve just had a court dress in red satin made. You can see it in the Evening at Hampton Court programme.

TT: Who would have made the clothes then?

TR: The linen would have been made at home – Katharine of Aragon even sewed Henry VIII’s shirts. But for the finest clothes, you’d employ a tailor – always a man. Lower ranks than the nobility would have made what they could. Clothes were recycled. Henry would give his clothes to his gentlemen, who would pass them on to their servants, and eventually they ended up on the poorest people. The fabrics might be cut up and used for other things as well.

TT: How important was dress?

TR: It was vital to nobles – everything was about display, how much you could afford, what fabulous fabrics you could buy, how much of a train you could afford to have dragging on the ground. There were Sumptuary Laws that said what colours and fabrics you could wear, and you had to pay a fine if you broke the rules. That was one of the ways you could show your wealth, too. “I’m rich enough to pay the fine.” One of the charges against Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was that he had clothes that only a member of the Royal family could have. Only royalty were supposed to wear purple.

Black was very expensive because you had to dye it over and over again to get it dark – there were no black dyes. Only very rich people could afford that. Dyes were fixed with urine, so clothes did not always last that long. And slashing to pull the fabric through was also a sign of wealth – you could afford to replace your silk or linen undershirt when it frayed.

When you wear the clothes, you become very conscious of how different ranks behaved, and rituals like taking your hat or “bonnet” off, or putting it on were important. You always took your bonnet off in the presence of someone of higher rank. He would then take his off, to be polite and put it back on immediately. If someone put his bonnet on before you did, you could take that as a sign that he thought he outranked you – that’s the sort of thing that led to brawling and duels.

Fashion was even important in armour – you can see armour decorated to look like slashed and puffed clothing, or even painted black to imitate the most expensive clothes. It was all about display.

TT: That is all absolutely fascinating – thank you for talking to Tudor Times.