Elizabeth of York: Sanctuary & Royal Residences

Elizabeth lived in an era when domestic architecture was changing rapidly. The homes of her childhood – the old palace of Westminster and vast castles like Windsor and Kenilworth, were giving way to the Renaissance styles of Eltham, Richmond and Greenwich. She spent the majority of her time in and around the palaces of the south-east of England, although, once Queen, she travelled throughout the southern counties on progress with Henry.

The numbers against the places correspond to those on the map here and at the end of this article.

Elizabeth first saw the light of day at Westminster Palace (1). Then, as now, Westminster was the seat of English government. From the mid-fourteenth century, the various administrative offices of the Crown had begun to settle there, instead of moving with the monarch. Westminster was therefore the only house owned by any of the mediaeval or early Tudor monarchs called a ‘palace’.

The palace, which had gradually grown over time, was centred on the magnificent Westminster Hall, built by Richard II, and still in situ. It once had the widest span of any building in Europe, and was a tourist attraction for foreign dignitaries.

Elizabeth spent much of her childhood in the palace, and it continued to be the chief royal residence throughout her life. It was in Westminster Hall that Elizabeth waited for the procession to form up for her coronation, and it was there that she presided over the subsequent banquet. Her eldest daughter, Margaret, Queen of Scots, was born at the palace in 1489, although an outbreak of measles required Elizabeth and the baby to leave as soon as they were able.

Westminster Palace was partially destroyed during the reign of Elizabeth’s son, Henry VIII, when in 1512, a fire ripped through the royal apartments. Henry VIII did not rebuild the palace, preferring to spend his time at Greenwich, or, later, at his new Palace of Whitehall.

Another of the royal residences where Elizabeth spent considerable amounts of time, both as Princess, and later as Queen, was Sheen (2). Sheen as a name still exists, in south-west London. In Elizabeth’s time, it was well outside the city, and reached usually by barge, although, coming from Westminster, it was possible to cross the Thames at the Lambeth ferry and ride along the south side of the Thames on the Portsmouth Road, now known as the A3.

The original house at Sheen was demolished by Richard II, overcome by grief at the death there, in 1394, of his wife, Anne of Bohemia. Nearly twenty years later, it was chosen by Henry V as a location for a new residence. It was to be complimented by the great Abbey of Syon, one of the last abbeys occupied by women and men, and presided over by an Abbess and the Priory of Sheen. Syon was dedicated (amongst others) to St Bridget, and was favoured by all English monarchs, including Elizabeth’s parents and Elizabeth herself, up until the Dissolution.

After the convent was suppressed, the nuns re-grouped in Europe, briefly returned during the reign of Elizabeth’s grand-daughter, Mary I, and were given licence to leave by her other grand-daughter, Elizabeth I. The community returned to England in 1861 and is now located in Devon – the only pre-Reformation house to have continued in unbroken line. The original Abbey estate was granted first to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, then by the Crown to Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, whose descendant, the 10th Duke of Northumberland retains it as his London home.

Sheen itself was built in a new style – separating the royal lodgings from those of the rest of the court. Elizabeth and her sisters were frequently there, in the care of their Lady Governess, Margery Berners. Sheen was a favourite location for Elizabeth and Henry and it was at Sheen that their daughter, Mary, later Queen of France, was born. Elizabeth was at Sheen when news came to her of the approaching Cornish rebels in 1497. Henry sent bodyguards to escort her from Sheen to Eltham and on into the walled city of London. Shortly after, it was at Sheen that she received Lady Katherine Warbeck, wife of the man who had claimed to be her brother, Richard of York.

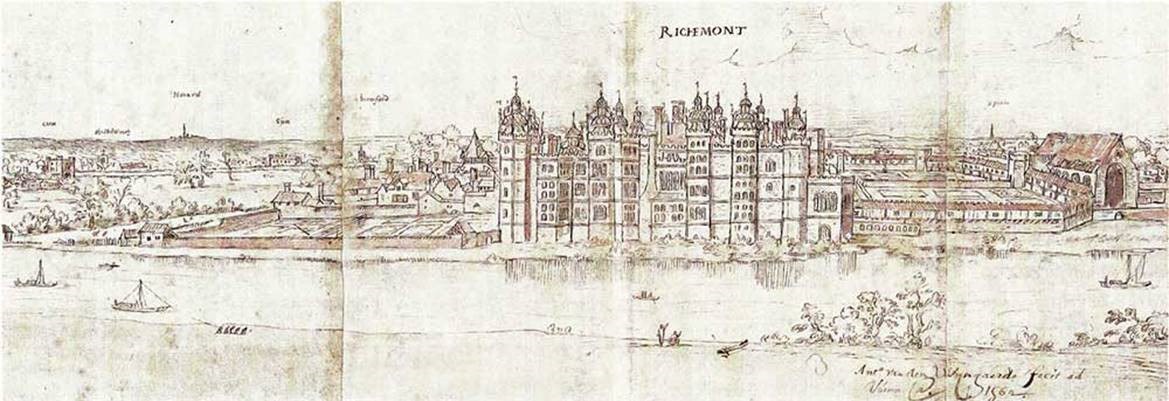

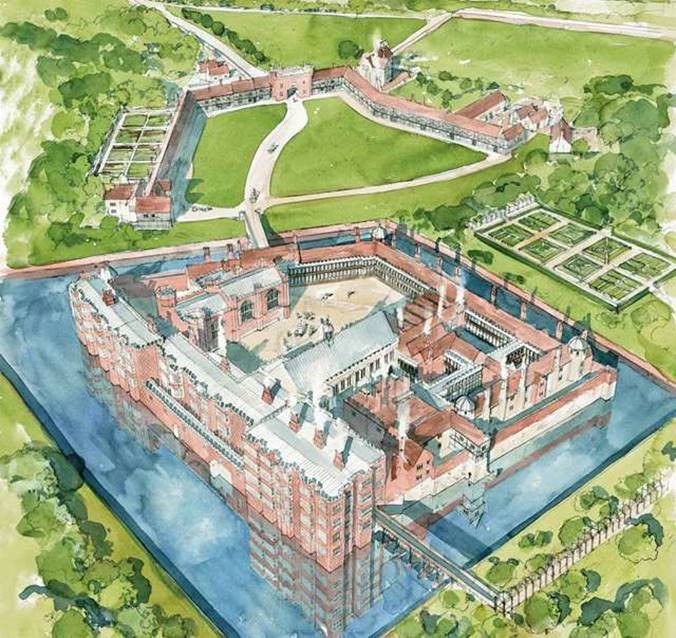

In November 1497, Sheen was badly damaged by fire. Henry immediately began rebuilding it, renaming the new house Richmond, from his pre-accession title of Earl of Richmond. It was largely finished by 1501 and Elizabeth, Henry and their younger children spent that Christmas there. In January 1502 it was the location for the proxy marriage of Elizabeth’s daughter, Margaret, to James IV of Scotland.

As part of the rebuild, new gardens were laid out. They included

‘royal knots, alleyed and herbed [with] many marvellous beasts, as lions, dragons…properly fashioned and carved in the ground…with many vines, seeds and strange fruits…’

Elizabeth had intended to give birth at Richmond in 1503, but her labour began whilst she was visiting the Tower, and she never recovered. Henry spent much of the rest of his reign there, dying at Richmond in 1509. It was a favourite palace of Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon. Perhaps it was always associated in Henry VIII’s mind with Katharine, as after the mid-1520s he spent much less time there. His daughter, Mary, visited it frequently during Henry’s reign, until it was given to Anne of Cleves as part of her divorce settlement. It reverted to the Crown, and Elizabeth I died there in 1603. Richmond was sold after the Civil War for £13,000 and soon demolished. Traces of Richmond’s gate house can still be seen in Richmond Park.

During her childhood, another of Elizabeth’s locations was Eltham in Kent (3). Eltham was much favoured by all the English kings from Edward III onward, and Elizabeth’s father, Edward IV, undertook extensive renovations and improvements. The old Great Hall was demolished and a new one built, facing onto a courtyard, which was approached by a stone bridge. Eltham was the first English royal residence to have the tall bays jutting out from the façade which we associate with buildings of the Tudor period. It was also one of the earliest to be built partly in brick – a very expensive option at the time.

The Christmas court of 1482, when Elizabeth was sixteen, was held at Eltham. Elizabeth’s younger children spent most of their time at the house, and Elizabeth visited them here frequently. It was the scene of Erasmus of Rotterdam’s first meeting with the young Henry, Duke of York, when the latter was ten.

Henry VIII continued the embellishments of his grandfather, adding a tilt yard in 1517, new royal lodgings and a chapel. Both his daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I, spent time there in childhood, although there is no evidence of Edward VI being housed there. Henry lost interest in Eltham after the mid-1530s, concentrating on Hampton Court, Nonsuch and Whitehall. Eltham, too was sold off after the Civil War and fell into decline. It was rescued by the Courtauld family in the twentieth century, and new buildings and superb interiors in the Art Deco style were created, and Edward’s Great Hall renovated. Now in the care of English Heritage, Eltham is open to the public.

One of Elizabeth’s earliest memories may have been of Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury, Kent (4). It was there on 8th June 1479 that she and her mother met her father for a service of thanksgiving, after Edward had escaped from the control of the Earl of Warwick, following the defeat at the Battle of Edgecote.

Canterbury was, and is, the parent cathedral of the English Church and now of the whole Anglican Communion. Dedicated to St Augustine, during Elizabeth’s life it was the scene of regular pilgrimage from all over Europe, to the tomb of St Thomas Becket. His shrine was covered with gold and precious gems. Elizabeth herself later made offerings at the shrine, and in the March before she died, two priests made offerings there of 5s at the altar of St Thomas, and a further 5s for Our Lady of the Undercroft.

The silver font from Canterbury was brought to London for the christenings of Elizabeth’s younger children, and later it was to be used for those of some of her grandchildren. Canterbury is still one of the great tourist sites in England - the enormous nave dates from around 1375 - 1400 and the Trinity Chapel (1175 – 1184) houses superb stained glass. In the archives and library are some of the great treasures of English literature – an early Bestiary, a First Folio of Shakespeare and a 1602 edition of Chaucer. It also contains a copy of William Tyndale’s ‘Obedience of a Christian Man’, which was one of the texts that influenced Elizabeth’s son, Henry VIII, in the development of the English Reformation.

Elizabeth was a daughter of the House of York. One of the most important occasions of her childhood was the re-interment of the remains of her grandfather, Richard, Duke of York, and her uncle, Edmund, Earl of Rutland. York had been killed at the Battle of Wakefield and his son, aged only seventeen, butchered by Lord Clifford, in revenge for the death of Clifford’s father at the Battle of St Albans. The victorious Lancastrian Queen, Marguerite of Anjou, had ordered that York and Rutland’s heads be placed on spikes over the gate of the City of York.

In 1476, five years after what seemed to be the ultimate victory of York over Lancaster, Edward IV arranged an elaborate ceremony in which York and Rutland were interred in the York family chapel at St Michael’s, Fotheringhay (5). The nearby castle was one of Edward’s favourite homes, outside London, and Elizabeth probably visited it frequently. It formed part of her jointure lands, and those of all her daughters-in-law.

Another of the great royal castles that Elizabeth knew well was Windsor Castle (6), to the west of London. Windsor is still the official home of HM The Queen, and it was a favoured location of Elizabeth’s parents. Edward built the superb St George’s Chapel as a home for the Order of the Garter. Elizabeth herself was inducted as a Lady Companion of the Order in 1477, aged 11. She took part in the annual Garter ceremonies for most of her life. In 1483, the Chapel was the location of her father’s burial. Her mother was also interred there, as was her son, Henry VIII, and her daughter-in-law, Jane Seymour.

Following the death of Elizabeth’s father, her brother, Edward V, was swiftly brought from Ludlow, where he had been presiding over the Council of the Marches of Wales. He was taken to the Tower of London (14), apparently in preparation for his coronation, but that never happened. Instead, the young King, Elizabeth and their siblings were declared illegitimate, and their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, took the throne. Elizabeth’s mother, the Dowager Queen, took Elizabeth and her younger siblings into sanctuary at Westminster Abbey (15), where they remained for some months. Her second brother, Richard, joined Edward in the Tower, and neither were seen again after the summer of 1483.

Eventually the Dowager Queen, Elizabeth and her sisters were persuaded to leave sanctuary. Where they lived afterward is uncertain. Elizabeth herself was at court in the retinue of Queen Anne Neville for the Christmas season of 1484. The following summer, Richard, anticipating invasion from Henry, Earl of Richmond, sent Elizabeth and her cousins, Edward, Earl of Warwick and Margaret of Clarence to Sheriff Hutton Castle, in Yorkshire (7).

Sheriff Hutton had been part of the great Warwick estates that came to Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, in right of his wife, Anne Beauchamp. Anne’s daughters, Isabel Neville and Anne Neville, married Edward IV’s brothers, George of Clarence, and Richard of Gloucester (later Richard III). In an unseemly squabble between the brothers, later exacerbated by the appalling treatment of Countess Anne, the lands were divided. Richard received Sheriff Hutton and used it extensively as his brother’s lieutenant in the North.

In the sixteenth century, it was the base for Elizabeth’s grandson, Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Richmond, in his role as Lord President of the Council, but it gradually fell into disrepair. The remains of the castle are located about ten miles north of York, just off the A64. It is privately owned, but access to the ruins can be arranged.

Richard III was defeated at the Battle of Bosworth. One of the first things Henry VII did was to send Sir Robert Willoughby to Sheriff Hutton to fetch Elizabeth. She was escorted honourably to Coldharbour (8), a London house in the ownership of Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, who would shortly become her mother-in-law. Coldharbour had once belonged to the Dukes of Exeter, but had come into the possession of Henry V. It had been granted by Richard III to his new College of Heralds, but Henry assigned it to Lady Margaret within days of becoming king.

It was to Coldharbour that Elizabeth initially took her children in 1497 when the Cornish rebels were marching on London, before they retreated to the Tower. Today, there is no trace of Coldharbour, but it was roughly east of Cannon Street Station, under the modern Queen Victoria Street.

Elizabeth married Henry VII on 18th January 1486. She fell pregnant immediately (perhaps even before the ceremony had been conducted). Henry, in his vision of creating a new, united country, with Lancaster and York joined forever in harmony, decided that his first child, whom he anticipated would be a son, should be born at Winchester. Winchester was, in fact, the Saxon capital of Wessex, but most people believed then that it had been the site of the British King Arthur’s Camelot. In the first years of his reign, Henry frequently emphasised his alleged descent from Arthur.

The Queen arrived in Winchester by the end of August, and took up residence in St Swithun’s Priory (9), rather than the Norman castle, built by William the Conqueror, the thirteenth century Great Hall of which is still extant. On 20th September, Elizabeth fulfilled her primary function, as it would have been seen at the time, by delivering a son. He was christened a few days later in the adjoining Priory Church, probably in the stone font which came from Tournai in around 1200.

The Priory Church, founded in the 640s, was re-founded as Winchester Cathedral in 1541. It is one of the oldest foundations in the whole of the British Isles. The original Saxon minster was rebuilt by the Normans, and is the burial place of William II Rufus, and of the great novelist, Jane Austen. Winchester Cathedral was the location of the wedding of Elizabeth’s grand-daughter, Mary I, to Philip II of Spain, in 1554.

Another of the houses favoured first by her father, and then by Elizabeth, her children and grand-children, was that of Placentia (10), in Greenwich. Originally a manor house owned by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, on the south bank of the Thames, it was extended by Henry VI and Edward IV. Elizabeth was at Placentia immediately before her coronation – it was from here that a barge took her to the Tower of London before her formal entrance into the city. Placentia was the birth place of Elizabeth’s second son, Henry, later Henry VIII.

In 1498, Henry and Elizabeth began renovations at Placentia, but by the turn of the century, they had decided to do something far more comprehensive. Elizabeth herself created the design, which the King’s mason, Robert Vertue, was commissioned to fulfil. By 1501, the old house had been demolished. Elizabeth’s plan included two long ranges – the King’s Lodgings and the Queen’s Lodgings; the King’s fronting the river, and hers parallel, but facing south, across a courtyard. The west ends of the two blocks were joined by a gallery, which also gave access to the Church of the Observant Friars. Elizabeth’s design was strongly influenced by the Burgundian taste her father had introduced into English architecture. 600,000 bricks were made for its construction.

Sadly, Elizabeth did not live to see it completed, but Greenwich became a favourite home of Henry VIII in the first half of his reign. Her grand-daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, were both born there. Under James VI & I and Charles I, the new Queen’s House was developed – the original design was for Anne of Denmark, but it was completed for Henrietta Maria. After the Civil War, Charles II planned to rebuild it, but could not afford to complete it. His works were taken over in 1695 by the Royal Hospital for Seamen, later the Royal Naval College and now house the University of Greenwich.

Elizabeth was truly mediaeval in her religious outlook. She made regular offerings to saints and relics, and visited shrines either in person, or via proxies. One of the greatest of the mediaeval pilgrim locations that she visited more than once was the shrine to the Virgin at Walsingham, in Norfolk (11). The chapel was probably built in the 11th century when a local noblewoman, Richeldis de Faverches, saw a vision of the Virgin. She was commanded to replicate the Virgin’s house in Nazareth. A priory was established by Richeldis’ son, and the shrine grew in popularity throughout the Middle Ages.

Many English monarchs and nobles had visited the shrine, including both of Elizabeth’s parents. She herself made her first recorded pilgrimage there in 1497, and sent two priests there on her behalf. Henry also visited the shrine, and, later, both Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon went on pilgrimage there. Anne Boleyn talked of doing so, but there is no record of the visit being made. The shrine was dismantled in 1538, and the statue of the Virgin burnt. Walsingham was re-established as a place of pilgrimage in the twentieth century, and there are now Anglican, Roman Catholic and Orthodox shrines there.

Not far from Walsingham is Oxburgh Hall (12), home of Sir Edmund Bedingfield. Bedingfield had been a supporter of Edward IV, but declined to take part in the Battle of Bosworth. Following the Battle of Stoke, at which he supported Henry, the King, the Queen and Lady Margaret Beaufort visited him at Oxburgh. It is likely that Elizabeth would have visited a second time when travelling to Walsingham.

As queen, Elizabeth travelled fairly extensively with Henry. As well as to Norfolk, and the royal properties in the Thames Valley, they also made several progresses to the Midlands. During 1487, when Henry was expecting invasion from Elizabeth’s cousin, the Earl of Lincoln, and Lambert Simnel, both Elizabeth and Arthur moved to Kenilworth Castle, where Henry was concentrating his preparations for defence. Kenilworth, part of the great Lancastrian inheritance of Henry IV, is now a beautiful ruin.

Ten years later, Elizabeth took refuge from another rebellion, this time in the Tower of London (14). The Tower had less of a sinister reputation then, than later, and mediaeval kings regularly spent time there. It was, of course, the last known abode of her brothers, Edward V and Richard, Duke of York. It is hard to believe that Elizabeth could ever have gone there without thinking of them, but she did visit from time to time. She went again in January 1503, intending to return to Richmond to give birth, but went into labour early. After giving birth to her last child, quickly christened Katherine, Elizabeth rapidly declined, dying in the Tower on her birthday, 11th February.

The funeral procession took her hearse through the streets of London, where the citizens mourned her sincerely. Her life had come full circle – from Westminster Palace where she was born, to Westminster Abbey (15), where she was interred. Twice Westminster Abbey had been a refuge for Elizabeth, where her mother had taken her to seek sanctuary, and now she would rest there forever. Henry had already begun the great Lady Chapel which bears his name, and in this mausoleum to the Tudor dynasty, Elizabeth lies, under the exquisite bronze tomb created by Pietro Torregiano.

The map below shows the location of the places associated with Elizabeth of York discussed in this article.